The flat of Jiřina Šiklová

“After the revolution, no one here knew what gender was, and those who had an idea about feminism perceived as an unacceptable ideology. We all had our portion of women’s equality fed to us by professional committee ladies, but we all hated it. So no one was interested in the women’s question, that was frowned upon. But then came the Americans Ann Smitow and Ruth Rosen (…) who worked towards starting an organization focusing on women’s position in society (…). Let me tell you a charming story about this: Ann and I want to start a bank account for Gender Studies so we go to a large bank in the centre, and the lady behind the counter just can’t get it and keeps asking me which one of us is Mrs. Gendr.”

(Jiřina Šiklová in an interview with Kateřina Jonášová, Hnízdo feminismu [The Feminist Hive], 2021)

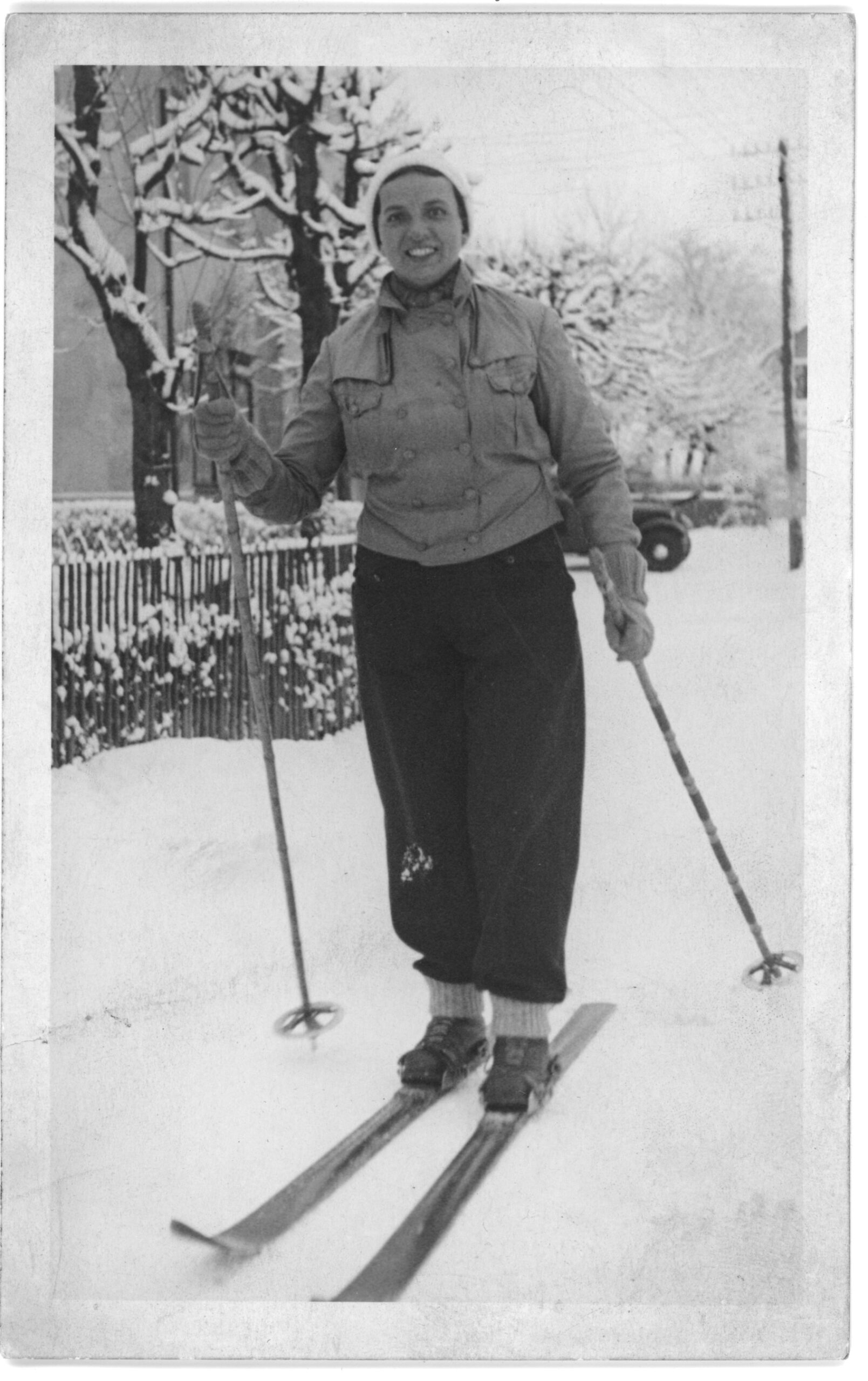

Jiřina Šiklová in her study on Klimentská Street

2010, Archive of Jana Hradilková

Photo: Jan Dufek

The library Klimentská Street 17 dates back to the summer of 1991, when Jiřina Šiklová invited Jana Hradilková to help systemize its work. As she recalls it:

“She drew me in quickly and straightforwardly: I could tell she needed me. Her first question, and actually the only qualifications she tested, referred to my written and spoken communication skills in English. And then to be always on my guard. To create, serve, respond, make quick decisions. In my own way. To not bother her with the how’s. How good it felt to have such a boss! On the very first day I already found a lot of things crazy. For example, there was a fascinating big black book in the room called the seam – namely her bedroom – that looked like an early 1900s registrar’s book. She showed it to me to prove something that sharply contrasted the overflowing bookshelves, namely her absolutely original systematic sense: she recorded in the book every incoming letter and every reply to it. And there were a lot of those every day! Letters were initially one of my central duties; I was to write and post so-called mendicant letters, but more importantly, to write Jiřina’s replies to all kinds of individuals abroad, many of whom I would later meet in person.

I attended my Klimentská office twice a week from morning till night. On my other days, I did what was necessary from my home. But Klimentská Street gradually became my second home.

Formerly an eye doctor’s surgery. A conspiracy den during the normalization era. In the 1990s, an open public-private space where the beauty of its mistress blossomed and transformed. A space for interweaving and sharing thoughts, ideas, agile initiating processes. To this day, I am amazed by the generosity with which Jiřina used and provided her space. It was a refuge for a highly diverse and cosmopolitan mix of people from all over the world. A uniquely charismatic mix of playfulness, wit, stimulation, provocation – yet in a context emanating sophistication and culture. This was a meeting place for different generations, professions, and cultural contexts.

The Klimentská Street flat became the home base for not only the Gender Studies but also a number of other associations – Promluv, La Strada, Profem, Jantar, Rosa, etc. Its active atmosphere was a given, with no room for idling. A constant flow of people during the day – young Americans, volunteers, all kinds of visitors –, they all had to be picked up personally downstairs and then again released personally when upon leaving – to this day, there is no buzzer for opening the building’s door. This ritual alone constituted a very strong element in strengthening relations. Indeed, it was often downstairs at the door that one experienced reconciliation after having obtained a somewhat tougher verbal lesson, or that a punchline was found for a phenomenon discussed back in the flat. I must add that even after the Gender Studies Library found its larger premises and relocated, I was allowed to keep the keys and continue attending numerous meetings, debates, gatherings, and team meetings. I could sing an entire eulogy on the processes the walls of this flat witnessed. The Klimentská Street flat was a hive of creative relations that comprised an invisible but robust, extremely broad, and colourful network – in short, social capital in its absolute form.”

(Jana Hradilková, February 2, 2023)

Listen to the whole story of Anna Kovář (Czech only)”We were looking for spaces where we could discuss and write... what was it like to be at the birth of the Nest of Feminism?

Jiřina Šiklová Library

Masarykovo nábř. 8, Praha 2 – Nové Město

The Gothic Revival apartment building at the embankment of Vltava River was designed by architect František Jiskra. With the neighbouring buildings no. 4 and no. 6 by the same architect, building no. 8 shares the same floor plan, river-facing façades with symmetrical bays, windows, and balconies and asymmetrically offset portals. Yet each building features different decorations, which contributes to a diverse riverside panorama.

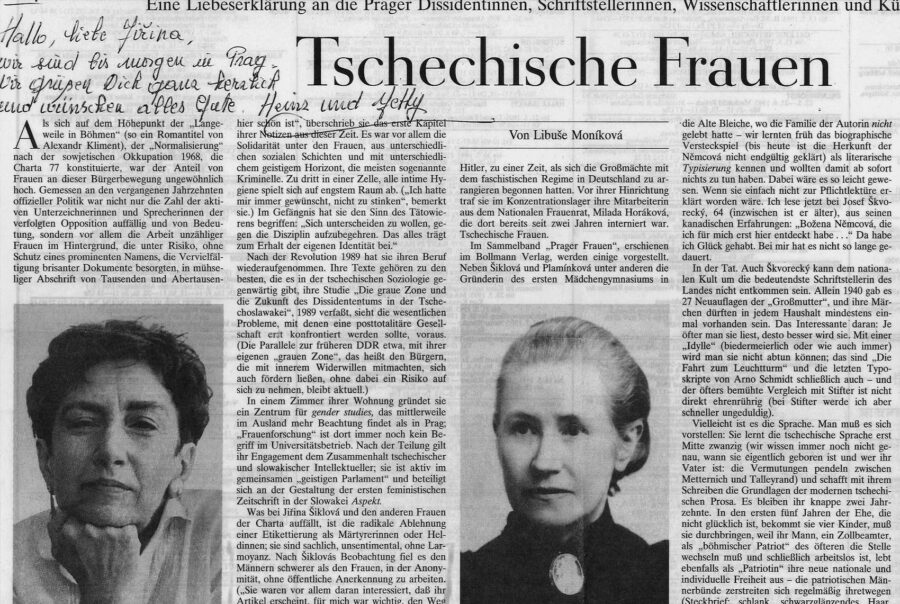

Moving on to the history of feminist Prague, the building contains the largest collection of feminist and gender literature in Central and Eastern Europe. The library was established in 1992 in the flat of the sociologist, dissident, and founder of Charles University Department of Social Work and Gender Studies, Jiřina Šiklová. It first comprised her private collection of feminist literature sourced from foreign donors such as University of California Santa Cruz, which had organized the Books for Prague donation campaign, or the U.S.-based Network of East-West Women. Later, the library also obtained the book collections of the lesbian organizations Promluv, Lambda, and A-klub. Funds to purchase books were historically provided by foreign foundations such as Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Open Society Fund, Open Society Institute, Network of East-West Women, and Global Fund for Women. The collections have been growing continuously thanks to project funds, mostly from EU institutions, and private donations. Nowadays, the Library offers a diverse portfolio of books and periodicals on gender stereotypes and discrimination, feminism, gender and queer studies. It also holds the Eliška Krásnohorská Archive (Archiv Elišky Krásnohorské), a publicly accessible collection of valuable archival documents on the history of the Czech women’s movement. Besides traditional research activities, the archived documents are also used for popularization efforts, including the extensive website www.zenymohou.cz. In addition to a part of the estate of Jiřina Šiklová, the library holds the Women’s Memory Archive of more than 170 oral-historical interviews with women of three generations telling their life stories against the background of the history the 20th century. The archive has been used in developing the educational portal, www.pametzen.cz.

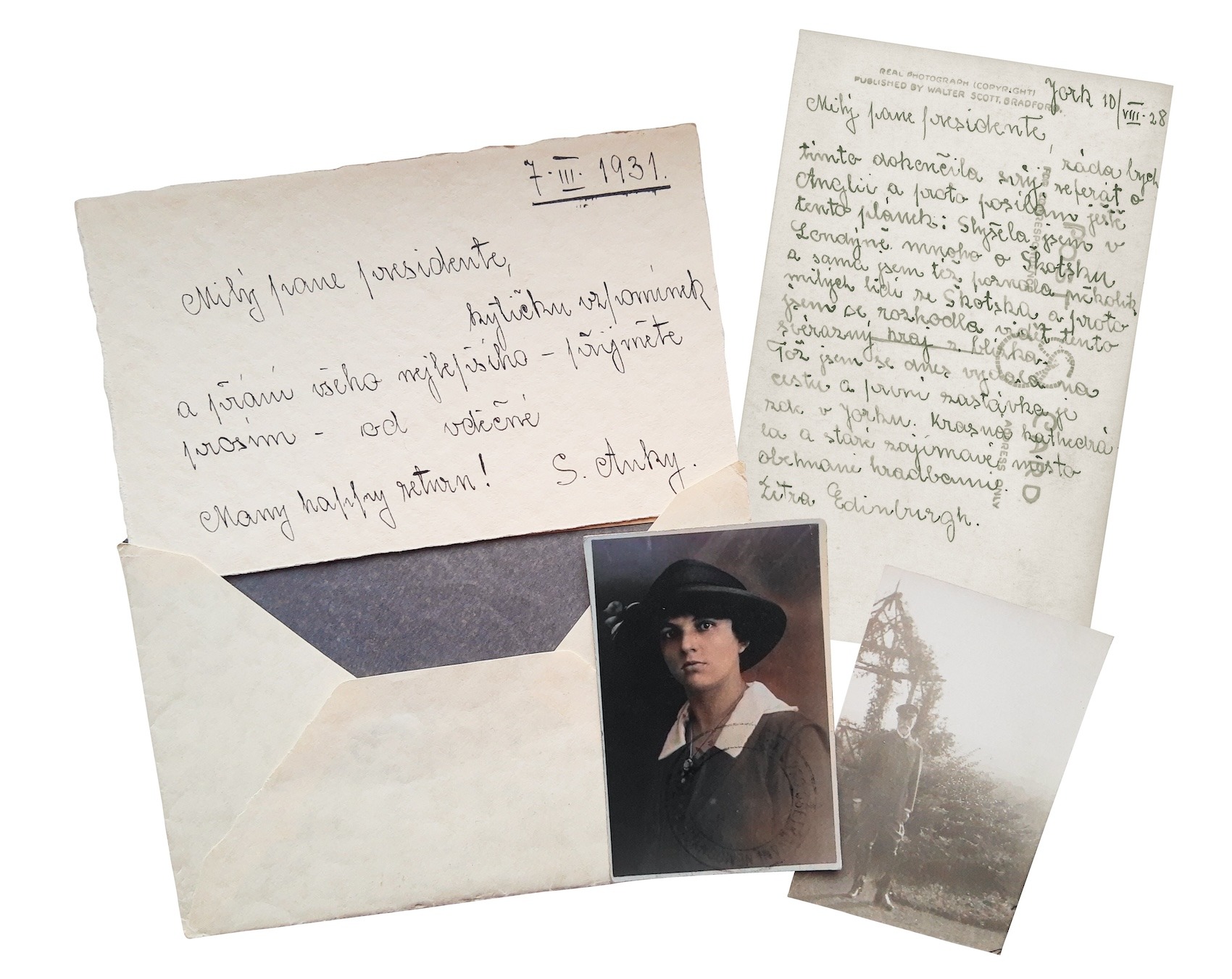

Eliška Krásnohorská Archive

The Gender Studies Library owns an archive of rare documents from the estate of Eliška Krásnohorská and from the early years of the Czech women’s movement. These materials are made publicly available. They were donated in 1997 by archaeology professor Jan Bouzek, a university colleague of Jiřina Šiklová and a relative of Vlasta Rostočilová. Vlasta Rostočilová collected and preserved memorabilia of a number of women’s associations, and she looked after her estate of their founder Eliška Krásnohorská. Jan Bouzek’s donation comprised the estate of Krásnohorská, valuable documents of the Czech women’s movement, and the estate of Vlasta Rostočilová. They are all parts of the Eliška Krásnohorská Archive preserved by the Jiřina Šiklová Library (renamed in 2021 in honour of its founder).

The Eliška Krásnohorská Archive contains unique documents, manuscripts, photographs, correspondence, author copies, contemporary periodicals, and other materials from the personal estate of Eliška Krásnohorská, women’s associations (Minerva, Women’s Czech Production Society, Women’s National Council, Czech Women’s Club), and other leaders of the women’s movement (e.g. Anna Rypáčková, Marie Calma Veselá, Vlasta Rostočilová, Marie Mikulová). A unique part of the archive is the photo collection of Soňa Hendrychová (born 1929), a Czech lawyer and the niece and secretary of Františka Plamínková. Thanks to her bequest, the Eliška Krásnohorská Archive also contains the photographs of Františka Plamínková, Milada Horáková, and other members of the Women’s National Council or the Czech Women’s Club. New donations and antiquarian acquisitions were gradually added to the Eliška Krásnohorská Archive, typically valuable archival materials covering the activities of the Czech women’s movement, especially from the mid 1800s to the 1990s.

In 2023, the Eliška Krásnohorská Archive underwent complete revision, restructuring, and digitization under the project From Eliška Krásnohorská to Jiřina Šiklová: In the Footsteps of Female Education conducted by Gender Studies in collaboration with Kvennasögusafn – The Women’s History Archives of the National and University Library of Iceland.

Jiřina Šiklová

(1935–2021)

sociologist, dissident, Charter 77 signatory, founder of the Department of Social Work and the Gender Studies Programme at Charles University

“Internalized social equality… No one even thinks anymore of asking a person about their class background. There has been a radical shift here. And a shift should also occur in the domain of gender, so that you don’t even think of asking someone whether they’re a man or a woman.” (Jiřina Šiklová in an interview with Kateřina Jonášová, Hnízdo feminismu [The Feminist Hive], 2021)

Known as a renaissance person, Jiřina Šiklová was active across several disciplines, including sociology, social work and geriatrics, politics, the dissent and literature, gender studies, and feminism. She engaged in establishing the Department of Sociology, the Department of Social Work, and the Gender Studies Department. She also established the library and NGO known as Gender Studies. She authored numerous books, articles, and research studies. “Those were peculiar times. New topics kept coming up; all one needed was to be assertive enough and to be in the right place. I also constantly maintained my freedom and ability to be where I wanted to be. But the nineties in general – they were an open space.”

She was born in 1935 as Jiřina Heroldová. Her father was a physician and social democrat, her mother a teacher. She grew up in a Klimentská Street flat that later became the central place of her life and work. In the same flat, she experienced World War II, including the disappearance of her Jewish neighbours or the building of barricades for the Prague Uprising. She earned a degree in philosophy and history at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University. After a brief episode of teaching at a primary school, she returned to her Alma Mater as a teacher. It was also where she co-founded the Sociology Department in the mid-1960s. Due to her interest in social policy, she entered the Communist Party in 1959, yet after the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, she became one of the teachers supporting student strikes. In 1969, she left the Party and then got fired from the university. Finding a job was difficult; while she typically worked as a cleaner, she continued holding consultations with her students. In the early 1970s, she found a social worker’s job at the geriatric department of one of Prague’s university hospitals. In addition to looking after her old patients, she also involved them in research activities, although she could not get published under her name.

In the 1970s, she joined the dissent, where she helped smuggle exile and samizdat literature and collaborated with a number of leaders, including Jan Kavan and Petr Pithart. She served as an important domestic liaison with a responsibility for pickups and distribution. She met with couriers to hand over shipments for exile publishers and she helped with the concealment and logistics of literature-smuggling cars. She was considered highly dependable. She transported valuable banned documents inside her coat, which came to be known as the smuggling coat. “It involved encoded letters, messages, sometimes essays, manuscripts on carbon paper. They weren’t books but things you could stick inconspicuously in your pocket. I had a coat with special pockets made for that purpose in case somebody searched me. When the police search you, they go over you from top to bottom, then the legs and unobtrusively at the crotch. But there are places – for instance at the knee, or the bottom – where they didn’t search. And that’s where I had a pocket cleverly sewn so they wouldn’t find it,” she recalled. She later signed Charter 77. In 1981, a motor home carrying one shipment of books was denounced, and Jiřina together with several collaborators got charged with subversion. She was jailed for smuggling books and remained in pretrial detention from April 1981 to March 1982. Although it was initially not clear how exemplary the court case would become (with a sentencing guideline of up to 10 years), sizeable international intercession led to everyone being released without a trial. Following her release, Jiřina Šiklová continued to organize book smuggling; instead of Jan Kavan, Vilém Prečan became her contact person abroad. He had built the Documentation Centre of Czechoslovak Independent Culture, which gathered exile and samizdat literature, at Schwarzenberg Castle in Scheinfeld, West Germany.

After the revolution of 1989, she returned to teaching sociology and helped establish the Social Work Department at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University, which she led until 2000. In addition, she initiated the establishment of a gender studies programme at the Prague university. She often met with female sociologists and feminists from abroad, who would bring her feminist and gender literature for the country. “In 1988, [a French journal] published a special issue on postfeminism. And the cops surprised me at home and confiscated it. I remember how they were asking me about it and I was telling them perfectly honestly: ‘I don’t even know what feminism is, let alone postfeminism.’ And it was through the Grey Zone, conversations with people from the West, the books I would receive by the dozen, that we decided to start an organization.” Thus, in 1991, Jiřina Šiklová along with Jana Hradilková, Marie Čermáková, Mirka Holubová, Pavla Frýdlová, and others founded the Gender Studies Centre and Library based in her Klimentská Street flat (nowadays known as Gender Studies, o.p.s., and the Jiřina Šiklová Library). This is how the renowned “feminist hive” came to exist. “When people ask why GS arose here, in Klimentská Street, I always tell them: because this flat had a flush toilet and hot and cold water, unlike the only other option in Karlín. It’s a joke but I think it gives one the idea.”

In 1995, she travelled to the World Conference on Women in Beijing via the Trans-Siberian Railway. After her return, she presented her idea of Women’s Memories, an international project to map the history of women’s emancipation in Central and Eastern Europe. I got the Woman of Europe Award and went to Beijing to that grand global women’s conference. I went by train and on the way, I realized that we had to change the way we do things, that our European perspective is very limited. I saw white women starring at women of colour with contempt. On that train, I would sit down with various women and talk to them because I was curious and spoke Russian. I saw the boundaries the women were drawing between one another, for instance how Russian women were patronizing other ethnic groups of the former Soviet Union. And I suddenly realized how gender issues are interlocked with ethnic and social issues. That’s why the idea of Women’s Memories was conceived on that train. Because I saw that there was no united stream of women. And this brings me back to Marx. If people’s social needs are not satisfied then we can forget about any higher-degree needs.

She is the author of multiple books: Omlouvám se za svou nepřítomnost: dopisy z Ruzyně 1981–1982 [I apologize for my absence: letters from jail 1981–1982] (2015), Vyhoštěná smrt. Úvahy o umírání a smrti [Death expelled: Thinking about Dying and Death] (2013), Stoupenci proměn. Studie o studentském protestním hnutí 60. let 20. stol. [Advocates of change: A study on the 1960s student protest movement] (2012), Matky po e-mailu [Mothers by e-mail] (2009), Dopisy vnučce [Letters to my granddaughter] (2007), or Deník staré paní [Old lady’s journal] (2003). She served on several governing boards (Vize 97, Charta 77 Foundation, and VIA Foundation) and on the editorial boards of scholarly journals in the country and abroad (e.g. Listy, European Journal of Social Work, East Central Europe, Social Research). She received a number of awards (e.g. Woman of Europe, 1995, Medal of Merit of the 1st Grade, the Alice Garrigue Masaryk Award for her services to the development of social work in the Czech Republic, 2000). In 2009–2010, she was also active in the Green Party.

Jiřina Šiklová has a daughter and a son. She was known for her vibrant energy, caring nature, and sense of humour. She died in the year 2021. In her honour, the Gender Studies Library was renamed to Jiřina Šiklová Library. In the same year, Gender Studies Organization published a book entitled Hnízdo feminismu [The Feminist Hive] based on one of Jiřina’s last interviews about her life and the history of the organization.

Marie Calma Veselá

(1881–1966)

opera singer, poet, writer, translator

“I didn’t write for fame, success, or profit;

like a bird, connected to nature,

I sang over the nests of men,

into their dreams and consciousness, into their daily routines,

of God’s beauty I sang my silent song,

lulling them, delighting, invigorating,

and with the sound of wings carrying them across the abyss.”

(The Gong, poem by Marie Calma Veselá)

Marie Calma was born in 1881 the town of Unhošť, into the family of Prague lawyer Matěj Hurych. She was a renowned soprano, opera singer, and modern music performer. Her stage name, Calma, originates from an Italian song. She had a reputation for her “rich silver voice”. She studied piano and singing at the Pivoda Singing School and as early as at the age of 17, she gave concerts in Prague, Vienna, Warsaw, and Munich. Later she married the physician František Veselý, founder of the Luhačovice spa resort, where she organized cultural events.

She wrote poetry, e.g. Písně moderní Markétky (1923), Jarní zpěvy (1929), Ejhle člověk (1934), fairy tales (Pohádka o českých muzikantech, 1925), and prose, and also translated from French (e.g. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry or Simone de Beauvoir) or from Polish. She contributed dozens of feuilletons to the periodicals Lumír, Národní listy, or Národní politika. She lived a rich cultural life and was friends with Leoš Janáček (their mutual correspondence has been preserved to this day). In 1916, Marie Calma helped stage Janáček’s opera Jenůfa in the National Theatre, although she did not obtain the main part for which she had longed. In addition to Janáček’s works, she helped promote song cycles by other Czech composers – Ludvík Kuba, Vítězslav Novák, or Ladislav Vycpálek. She died in 1966 and is buried at Prague’s Olšany Cemetery.

Anna Rypáčková

(1895–1978)

“phantom of the hospitals”, first registered nurse, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk’s personal nurse

Anna Rypáčková was born in 1895 into a poor family in a small village near Bechyně, South Bohemia. At the age of 7, she became an orphan. Later, she went to live with her older sister in Vienna, where she experienced World War I. In 1918, she returned to Bohemia with a plan to become a nurse. She took on babysitting to make a living during her nursing studies. After graduating from the Czech Nursing School in Prague’s Ječná Street, she became the country’s first registered nurse in 1924. From 1925, she served as a personal nurse to President Masaryk. They became pen friends (she signed some of her letters from Great Britain informally as “Miss Anky”). Anna learned a lot during her London scholarship, where she attended the 1937 International Congress of Nurses in London. She was an active member and later chair of the Association of Registered Nurses.

Under German occupation, she worked as a healthcare professional, delivering packages to the prisoners of Terezín, ensuring financial support for their families, and also hiding prosecuted people from the Gestapo. However, following an arrest in 1942, she got sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison for her activities. She was incarcerated in Prague, Waltheim (near Dresden), and Terezín (where she nursed prisoners at the Small Fortress) and in the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. After the liberation of Czechoslovakia, she returned to Prague’s General University Hospital as its civilian head nurse (later she was promoted to head nurse, a position formerly reserved to nuns). In that capacity, she organized educational courses and scholarly lectures for hospital staff, helped other women obtain education, and initiated the opening of new nursing schools. She was also active in the labour union. In 1947, she undertook a fellowship in the U.S., where she gained additional experience. Back in Prague in 1948, she became the principal of a nursing school. She helped the needy all her life, looked after tuberculosis patients, cooperated with the Salvation Army, and became one of the first nurses to administer insulin to diabetes patients, thus allowing them to reintegrate in society. For her service, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal from the International Red Cross. She died in the year 1978.