“The purpose of the Women’s Czech Production Society in Prague is to pursue the improvement and expansion of women’s production, the beneficial marketing of women’s products, the material security and further education of women on the basis on mutual cooperation.” (Statute of the Society, 1871)

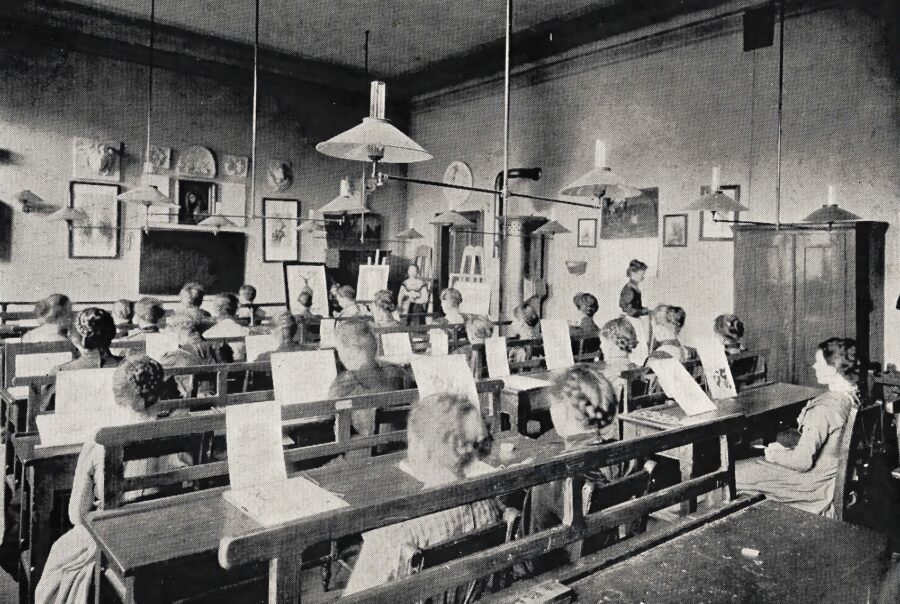

Women’s Czech Production Society (Ženský výrobní spolek český) was an educational and charitable association active in the years 1871–1972. Established by Karolina Světlá and Eliška Krásnohorská, it was one of the first women’s associations in Central Europe. The main goal of the Society was to establish a practical secondary school to teach girls skills useful in life. Here, girls attended lectures in business, industry, and craft disciplines to increase their chances on the labour market in case they did not get married or got widowed. They also obtained practical contacts for housing through a local advertising platform and were taught financial literacy with the help of savings banks. They also studied the arts of drawing and wood engraving. Among other women, Sofie Podlipská, Věnceslava Lužická, Ladislava Čelakovská, and Jindřiška Flajšhansová worked for the Society.

Places like the Women’s Production Society helped women obtain the necessary knowledge and skills for independent adult life. During its first twenty years of existence, as many as 10,000 members went through the Society, more than half of whom enjoyed free access to all activities after proving their lack of funds. In contrast to the American Ladies’ Club or the Minerva Gymnasium, even girls from poor families could afford education at the Society. The Society also established itself as an institution of strong social conscience. For example, it allowed young children to accompany their mothers during course attendance – something unheard of at the time.

In 1894, the association purchased the property of a former jail in Resslova Street and built a business-oriented secondary school for girls. The building was designed by architect Josef Blecha. The association’s activities slowly declined after World War I. Its Resslova Street building was damaged by a bomb raid in February 1945, and after reconstruction, it became a practical secondary school for international economic relations. The Women’s Production Society was merged with the Czechoslovak Women’s Union after 1948 and completely shut down under the so-called normalization in 1972.

In 1961, the communist party decided to dedicate the building to another practical secondary school, which is now known as the Czechoslavic Business Academy, Resslova 1780-II/8. The building’s front features the date 1896 in a tympanum and the words Ženský výrobní spolek in the axis of the second floor. The building’s front between the windows of the first and second floors features three busts in half-circle niches depicting presidents of the Society Emílie Bártová, Karolina Světlá, and Eliška Krásnohorská.

Listen to the whole story of Anna Kovář (Czech only)”Even women like us were allowed to join the Production Society. I was still in the cradle, but what did my mother learn here?

Karolina Světlá

(1830–1899)

one of the founding mothers of the Czech women’s movement, writer, rural life novelist

“We really do not wish more than for our ladies to find a good book as indispensable as a train behind their dress, with which they so selflessly sweep the streets of Prague.” (Karolina Světlá, Listy ženám o ženách II [Letters to women about women II]. Květy, 2, 1867, No. 7, p. 81.)

Real name Johana Nepomucena Rottová (Mužáková), born 1830 in Prague. She came from the Prague-based family of businessman Eustach Rott, who supported his children’s education from a young age. Writer and translator Sofie Podlipská (Žofie Rottová) was her younger sister. Later she married her music teacher, Petr Mužák, who lived in the Ještěd Foothills and introduced her to the patriotic circles. Her husband’s birthplace later inspired both her pen name and her literature. She maintained friendships with Jan Neruda and Božena Němcová. Her life was strongly shaped by the death of her only child, daughter Božena, at the age of three months.

She discovered her great literary talent in childhood and later developed it as a writer and journalist. Her most famous works include Little Black Peter, The Village Novel, Cross by the Brook, The Non-Prayer, Frantina, and Kantůrčice. In addition to her rural realist works, she authored the story behind Bedřich Smetana’s opera, The Kiss, with its libretto written by her friend, Eliška Krásnohorská. In her journalistic work, she primarily focused on the position of women in society. Karolina Světlá refused the patriarchal (men’s) rules of assigning social roles, just as she refused the term women’s literature or literature for women. “Let’s face it, are there two natures or two truths?” she asked in her diary. In 1867, she published the essay O vychování ženy [On raising women] in Květy magazine, considered one of the Czech lands’ first texts on the women’s question. She later joined the Women’s Letters, which were originally published as an appendix to Květy and then became the official publication of the Women’s Czech Production Society. Like her sister Sofie Podlipská, she integrated her patriotism with sports and a healthy lifestyle and she countered the era’s gender stereotypes by advocating for women’s access to sports, tourism, and healthy food. Her niece, Anežka Čermáková-Sluková, became her co-worker and penfriend, and later performed language editing and transcription for her literary works to compensate for Světlá’s acute eye disease. Anežka also ensured the preservation of Karolina Světlá’s estate and its depositing in the Podještědské muzeum (Ještěd Foothills Museum) of Český Dub.

She was an active member of the women’s emancipation movement. She and Vojtěch Náprstek co-founded the American Ladies’ Club in 1865. She helped start the Women’s Czech Production Society in 1871 and served as its director for the first couple of years. As its mission, the Society helped girls from poor families to obtain free education and learn an array of practical skills for their future gainful employment.

Emílie Bártová

(1837–1890)

women’s education and women’s suffrage advocate

“Improving women’s education is one of the most noble and justified demands of our days. It is with utmost respect that we the undersigned hereby raise this plea of ours to the esteemed Chamber of Deputies of the Imperial Council of Austria. Modernity has changed the face of the entire society. The woman is no longer exclusively the man’s protégée, her natural calling within the family has ceased to be her only destiny; millions of women are deprived of the safety of the hearth and home… cheap industrial products have replaced many types of women’s housework… Women both married and outside wedlock are forced to contribute their earnings to the man’s to ensure the sustenance of their own and their loved ones. Therefore, they have the full right to ask for professional education…” (Prague City Archives, the Women’s Production Society collection, Petition of Czech women to the Imperial Council of Austria, 1889)

Emílie Bártová, née Kalivodová, was born 1837 in Habry, a village near what is today Havlíčkův Brod. She was a Czech feminist, women’s education advocate, and suffragette. She also served as an active member of the American Ladies’ Club and co-founder of the Women’s Czech Production Society (later its president). In 1879, she assumed the Society’s presidency after Karolina Světlá and served in that capacity till her death in 1890. She also collaborated with Věnceslava Lužická, Sofie Podlipská, and Eliška Krásnohorská. The husband of Emílie, attorney Vojtěch Bárta, also helped Eliška Krásnohorská with the establishment of Minerva. He did so despite criticizing his wife for being overly eager and too involved in the women’s movement.

Eliška Krásnohorská

(1847–1926)

writer, initiator of women’s education efforts

“And the closer to Prague my train was getting, the clearer my mind was becoming. I was no longer saddened by mummy’s resistance to my departure; I had understood that every generation holds its era’s opinions, and mummy, too, quite naturally so, saw the callings and duties of a girl in an old-fashioned way, with dislike and distrust of the threat to order and orderliness posed by the spectre of “emancipation”, as personified by Karolina Světlá, to whom she was ascribing – not entirely unfoundedly – a central role in my decision.” (Eliška Krásnohorská, Co přinesla léta [What the years brought], Vaněk a Votava, 1928)

Eliška Krásnohorská (real name Alžběta Pechová, registered as Elisabeth Dorothea) represents one of the key leaders of the Czech women’s movement and initiator of women’s education efforts. She lobbied for the right of women to study at secondary schools and later also colleges. She co-founded the Women’s Czech Production Society (with Karolina Světlá) and initiated and helped establish the first girls’ gymnasium in Central Europe, Minerva. She wrote poetry books, prose, librettos for leading Czech composers, and theoretical papers, especially on women’s emancipation. A number of secondary schools, NGOs, and women’s rights events exist in her name to this day.

From a young age, she suffered from rheumatism, which prevented her from getting married. As marriage represented the era’s standard social mobility channel for girls, she was at risk of complete and permanent dependence on her married sisters or brothers, perhaps as their housekeeper. She graduated from the Svoboda Girls’ School, where she obtained not only practical skills and general education but also learned several foreign languages and gained an understanding of music. She played the piano and sang in the Hlahol female choir. Due to financial difficulties, her family relocated from Prague to Pilsen during her teen years. However, at the age of 27, Eliška decided to return to Prague, where she wrote for a living. She also attended lectures at the American Ladies’ Club and other educational events accessible to women.

She authored poems, novels, short stories, and librettos. Her famous works include the tetralogy Svéhlavička (“The Stubborn Head”), the poetry books Z máje žití, Ze Šumavy, and Ozvěny doby, as well as the memoirs Z mého mládí and Co přinesla léta. He also authored librettos for operas of Bedřich Smetana (The Kiss, based on a story by Karolina Světlá) and translated (e.g. Bizet’s opera Carmen from French). She wrote for the periodicals Osvěta, Lumír, Světozor, Zlatá Praha.

Thanks to her lived experience of an unmarried woman, she took great interest in the women’s question and advocated for the right to education and work. In 1871, she co-founded the Women’s Czech Production Society (with Karolina Světlá), in which even underprivileged girls were able to obtain education and learn practical skills. From 1875 to 1911, she served as editor-in-chief of the Society’s official publication, the Women’s Letters. She also inspired the efforts to establish the first girls’ gymnasium in Central Europe – Minerva, which materialized in 1890 (as a private school at first). Graduating from the girls’ gymnasium gave women access to universities, which was also one of Eliška’s goals. She played a role in legalizing women’s college education. After WWI, President Masaryk appointed her as the first woman regular member of the Czech Academy of Sciences and Arts. At the occasion of her 75th birthday in 1922, she became the first woman in the history of Charles University to obtain an honorary doctorate in philosophy. Eliška Krásnohorská died on November 26, 1926, at the age of nearly 80. She is buried in a family vault at Prague’s Olšany Cemetery.